I am playing Elden Ring these days. At start, all I got was lots of frustration, but currently, I am using it to de-stress. I know I will die every few minutes, so who cares? I die and chill, surprisingly. Until I will get bored and move on.

I keep asking myself: how would a f2p Elden Ring work?

First of all, let’s make assumptions about you, the potential players. They like rich lore, beautiful weapons, and big monsters. You decide to play on mobile while watching a Netflix show. Scroll and swipe a mobile game, to get endorphins while doing something passive. You don’t need too much cognitive effort, but you would put the show on pause to make a meaningful choice.

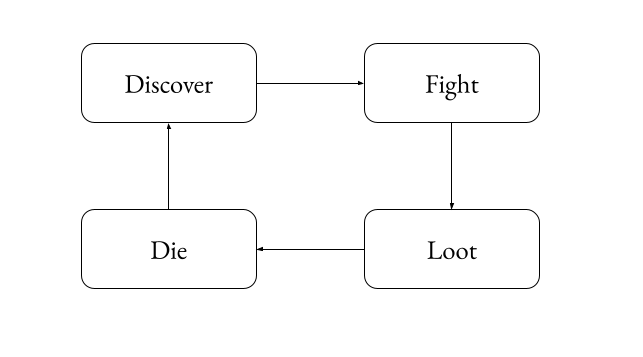

Core loop

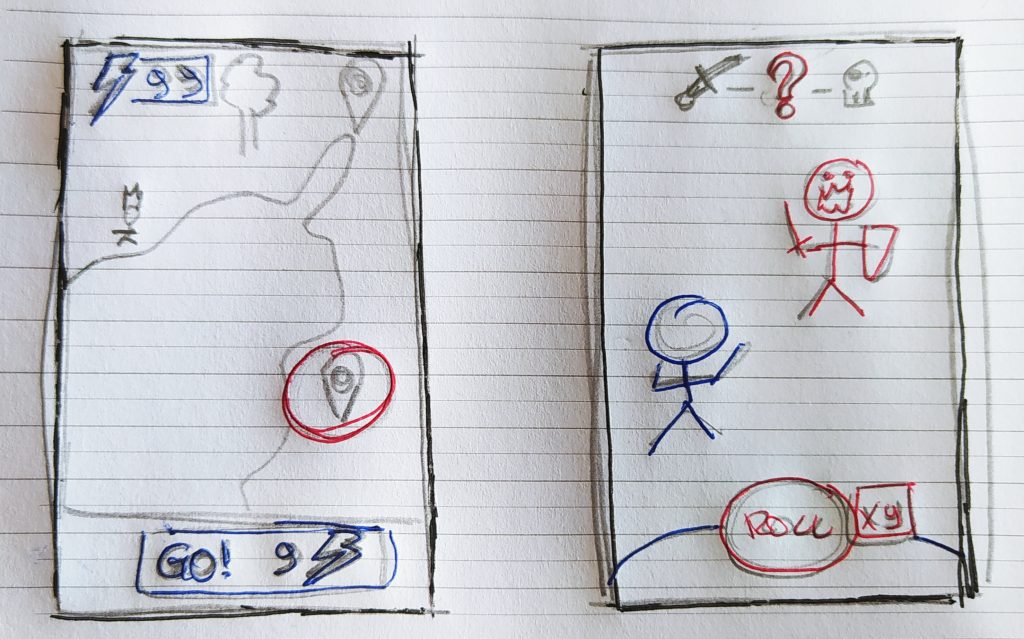

- The discovery is the most relaxing part of Elden Ring. You can choose the direction you want to go and the map is huge. In case you find a site of grace, you can upgrade your character here.

- The combat is too stressful for a mobile F2P game that wants to reach massive audiences. So what if you already know its outcome? You already know that in the next 3 fights, you will beat, beat, and die. Or, beat, random outcome (roll: beat or die), and die

- The loot is key because you do not lose your inventory when you die (only your runes)

- Death is the catharsis that lets you restart your discovery. You can choose to go retrieve your souls (at your own risk).

The long-term goal is to complete the adventure. The live operations should focus on adding more chapters, on one end. On the other, temporary events and special bosses to loot extra spells and swords.

The puzzle that brings you to return over and over lies in the choice of direction to take to discover and upgrade your Tarnished. You should engage with the community to find the right guidance, or you can decide to discover everything yourself.

Metagame

I like this idea of the Players already knowing that they will die. They can dedicate themselves to relaxing, exploring, and enjoying the combats. Combats should be automatic, the Player can choose the equipment.

The economy of the game should be around enemies, souls, stats, and equipment. You need souls to level up the stats. Stats are useful to use the equipment. The equipment is to beat the enemies. And the enemies give you souls.

Every part of the core loop should be monetizable. Discovery leans on energy systems. Combat has rolls and power-up opportunities. You can multiply the loot. Finally, death can be the occasion to recover the consumables you lost (energies, power-ups, …).