I joined a list of mentors in the games industry a while ago. I receive messages from all over the World that make me think a lot. Very grateful for receiving those energies from different cultures and people.

One of the most common requests I get is about how to write better design documents. The main issue with documents is the harsh reality that most people don’t want to read. Also if some of them have this duty, I have noticed that oftentimes they keep what you said in a presentation or chat. So, why boring to write a wall of text?

It’s important to write a lot on the game we are making, for ourselves. It is not important, instead, to write a lot for others to read. That is my point. I do like this.

- I start by writing by hand on paper. Very important to create meaningful connections in my brain. I don’t get the same result when I write on a keyboard.

- I continue by writing digitally a short resume of what I wrote on paper. Sometimes very short.

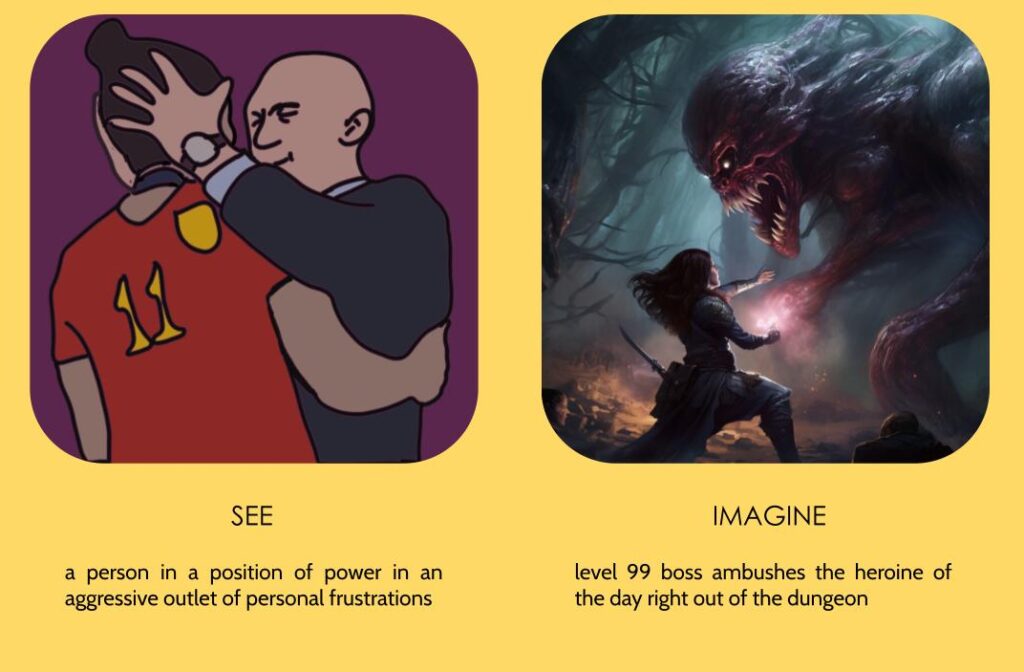

- When something needs more words, I create an image instead. It can be a flowchart, a UX flow, a wireframe, or a sketch.

- Then I read the document again in a loud voice. This makes me spot things that are hard to read. It has to be aloud. Don’t be shy, don’t be lazy. It doesn’t work if you read in your mind.

- If I have time, I try to add something fun to spot in the most boring parts. That happens very few times, honestly.