Loops are a great way to drive design discussions with everyone on the team. They are a simplified version of a flowchart and the last element connects to the first. I see that there are different definitions of loops and today I want to show you mine.

As with many other definitions related to game design, the fact that there are different versions implies often that you need to make an effort to understand the point of view of who’s driving the conversation.

Game, Core and Meta loops

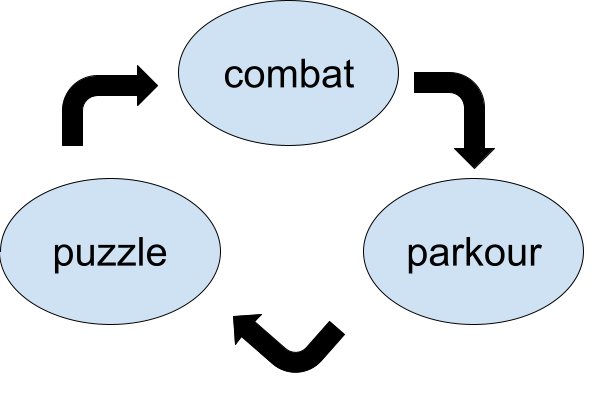

When I say game loops, I mean the sequence of most used features within the game.

- The example above represents an action-adventure game like Uncharted

- Every circle represents a feature, a collection of mechanics that creates one or more dynamics

- The arrows represent how the game is supposed to lead the Players to the next feature

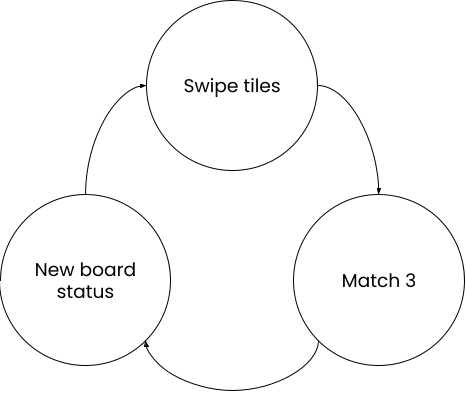

With core loops I mean the sequence of actions that the Player performs more often during the gameplay

- The example above is the core loop of a match-3 game

- Every circle represents a mechanic

- The connecting arrows can be read as “so that”: As a Player, you swipe tiles SO THAT you match 3 or more tiles you get a new board status SO THAT you can decide which tiles to swipe next.

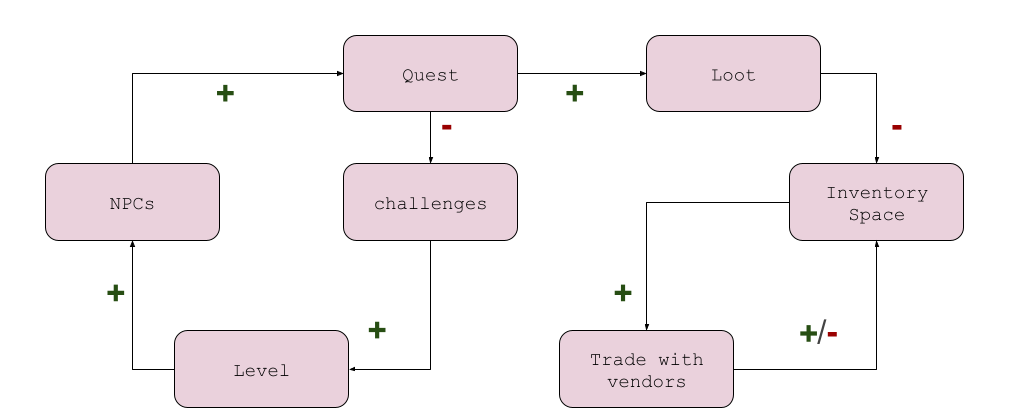

Finally, there are the metagame (or economy) loops, which represent the construction of the economy on top of the actions. A good economy makes you think about the game when you are not playing.

- the example above represent (a simplification of) a possible metagame for an RPG

- every rectangle represents a game feature, mechanic, or concept

- arrows indicate that a system adds or subtracts elements from the next rectangle. For instance, speaking to an NPC will increment the number of quests that the Player has. Collecting loot will remove inventory space.

Conclusion

There is not a single way of looking at loops, what is important as a designer is to have your voice. Oftentimes clients show me their “core loops” and in my definition, those are “game loops” instead. And there is no problem, the client is always right and I can adopt their jargon easily. The important is to keep my base strong to drive meaningful discussions.

Loops are useful to express concepts and drive discussions, they don’t have to be perfect. They are a medium for a concrete purpose: clarity. I saw very complicated loops, for instance, that do not add clarity. In that case is better to break it down into different feature loops (which are game loops that describe a single feature, when it’s too big).

Finally, the loops should be meaningful. Good loops have a long-term goal associated with them. You decide to repeat the loop over and over to reach that goal. So ask yourself what is the goal for every loop you identify.