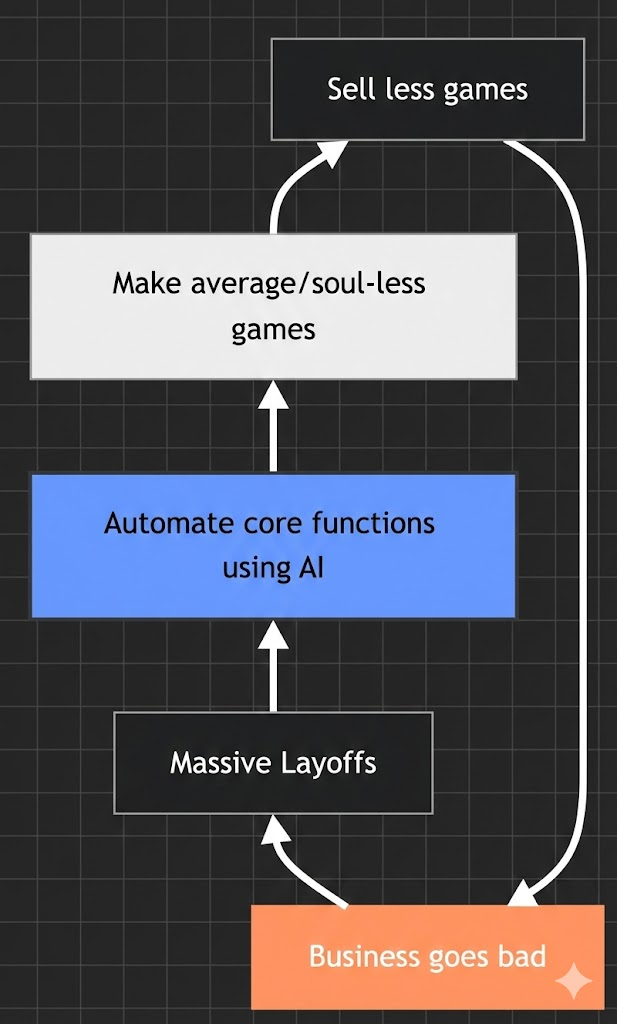

The recent news regarding Ubisoft isn’t just another headline about industry layoffs; it’s a “leading indicator” of a systemic crash. When the numbers don’t add up, the corporate playbook is predictably uninspired: cut the talent, automate the core, and pray the spreadsheet balances itself out.

But creativity isn’t an assembly line, Ubisoft might be the “canary in the coal mine” for an industry chasing its own tail. This isn’t just a trend; it’s a form of “drowning.” When inefficiency (ROI) drops too low, leadership grabs whatever is in reach—AI, NFT initiatives, or massive restructuring—often without even knowing what questions to ask their experts. They are borrowing against a future they don’t understand, hoping that money alone can catch the wind.

The “Glass Ceiling” of the French Elite

A company is only as brave as its leadership, and here we find a significant bottleneck. Ubisoft’s executive team is roughly 90% French, educated at the same elite business schools (ESSEC, ISG), with tenures spanning 30 years.

While these credentials are impressive on paper, they’ve created a cultural monoculture. This “upper-middle-class business elite” is now tasked with innovating for a global, diverse audience they are increasingly disconnected from. When leadership hasn’t seen the inside of another studio in three decades, they stop leading and start rehashing.

The AI Gamble: Partner or “Slop” Generator?

The debate around AI in development is often polarized. Someone argues that AAA gaming is “dead” without AI to reduce the staggering $200m+ budgets. I don’t disagree that budgets are exploding, but I disagree that AI is the silver bullet for quality.

AI isn’t the root of the problem, but it’s a risky “solution”. Relying on a technology that hasn’t yet delivered on its creative promises to save your strategy is a bet, not a plan. If you use AI to generate “slop,” you might save on costs, but you’ll lose the player.

From Rational Design to Brand Decay

Ubisoft once had a superpower: Rational Game Design. It was a method that allowed them to optimize the creation of epic adventures while maintaining a clear vision. But as they chased whales, “Games as a Service,” and unsustainable growth, they lost the creative DNA that made them special.

A software (and AI is just that) cannot solve a brand crisis. AI can’t fix the fact that Ubisoft has distanced itself from player fantasies and instinct—things that aren’t taught in prestigious business schools.

The Opportunity in the Chaos

The failure of long-term vision in these managers is an opening. The collapse of the old guard creates space for those who actually understand imagination and positioning.

Ubisoft’s stock may be back to 1998 levels, but the talent is still out there. The question is: will they be allowed to lead, or will they be replaced by an algorithm until there’s nothing left to automate?