I was watching the last Deconstructor of Fun podcast, shooter monthly, on Highguard.

I downloaded the game days ago, completed the tutorial and played three matches. I am not really into hero shooters, but I have to admit that I also had the sensation, as these expert say, that the game was not properly play tested. Which is a common issue in the industry that leads to many games to fail miserably. You need to engage with your future clients, especially with service games. You cannot simply launch early access anymore, early access in current market is perceived as a full launch, especially if you game has been announced in “pompa magna” at The Game Awards by Jeff Keighley in person.

Regarding the market segmentation

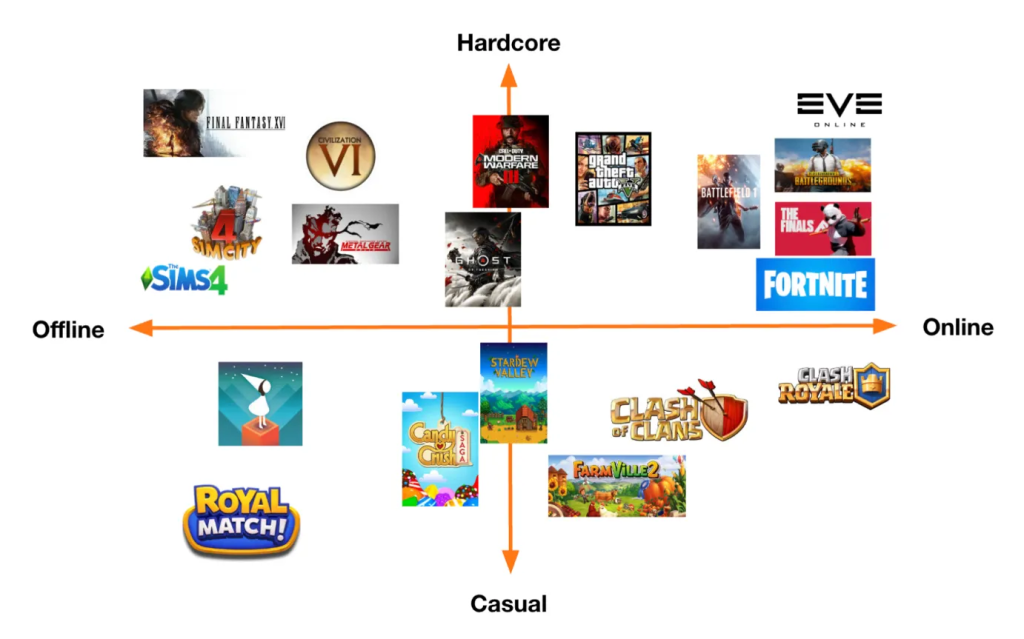

The experts seem to agree (but not fully) on the fact that there are just two kind of profitable shooter genres: tactical and battle royale. I am not sure about that, I prefer this Owen Mahoney’s segmentation:

I believe that shooter as a genre fits in at least 2 quadrants: online and offline hardcore. Nicholas Lovell also has his view on the industry in general.

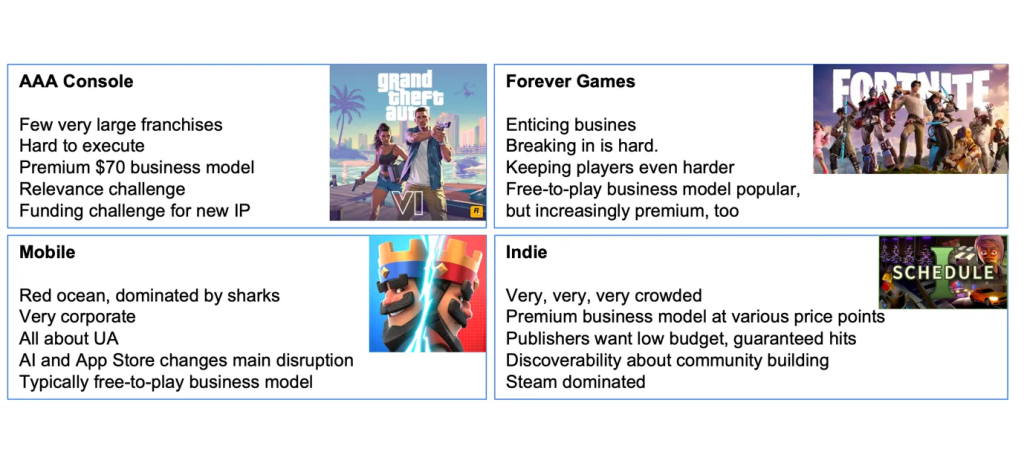

And we know there are AAA fps, forever fps like Fortninte, mobile FPS, and also indies who build on top of boomer shooters. Finally, there is Christopher Dring view of the industry:

Under this lens, I see games like STALKER being fps with stories. Fortnite and so on, are for socializing, but also competition/sport. COD and Battlefield as well. Boomer shooters are for passing the time, especially indies like this one.

I believe that the market is more complex and varied than the one pictured by Phillip Black in the DoF shooter monthly podcast.

What I do believe about the game modes

In the podcast, they insisted that the right number of people should be 5vs5 or 3vs3vs3, and I agree with them. But I believe that are also other problems with general game pacing:

- Mining crystal is not the best during a shooter session, in my humble opinion. I know it’s a basic in Fortnite, but there you can then build things instantly. Here, instead, is to buy stuff from a vendor.

- The vendor itself is slow and boring, can be put in another place

- Upgrading/reparing walls is not so exciting, too.

First idea I would try to pitch and eventually design is to buy weapons and repair walls when you die. You die and while you wait, your “soul” can repair stuff. I know, maybe you prefer to watch what is happening, but that can be an extra cam or something while you fix things.

Another thing I noticed is that the most exciting part is when you raid or you need to defend from a raid. Still, I had the feeling that the attackers, the raiders, were stronger than the defenders. Maybe it’s just psychological, but I would like to try something asymmetrical, like 3vs5 (5 defenders).

Running on the horse while shooting is also cool, I remember that from RDR2, which lead designer works for Highguard. Maybe there can be the moment of earning crystals instead of mining.

3 ideas I would pitch:

- Buy weapons and manage base on death

- Asymmetrical raids

- Earn crystals while killing people from the horse

Maybe these would create more exciting/unique moments for Highguard.